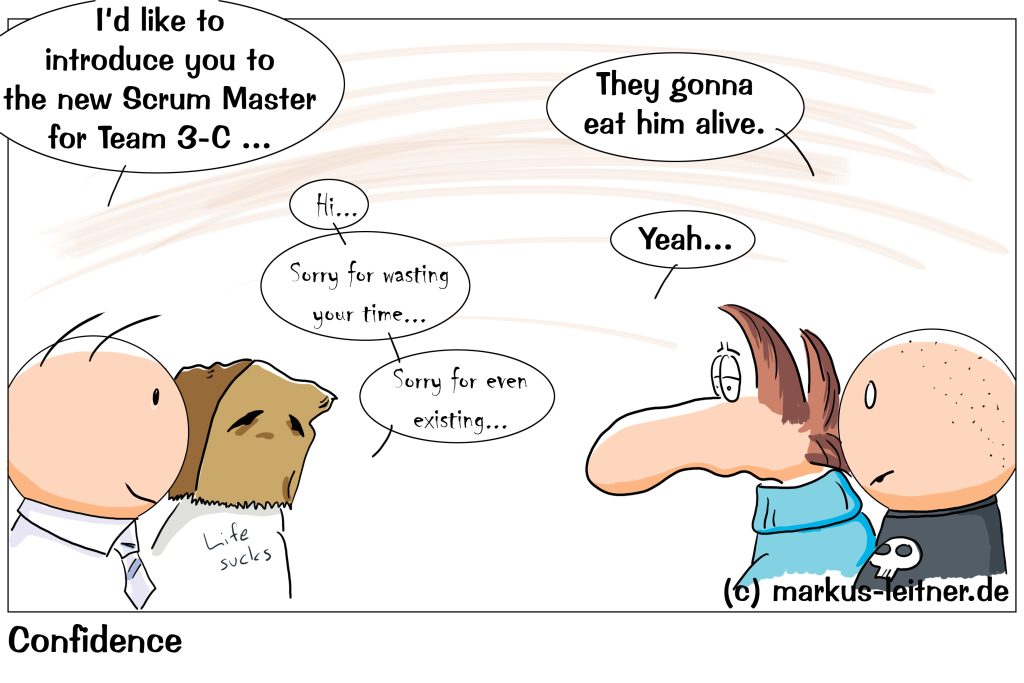

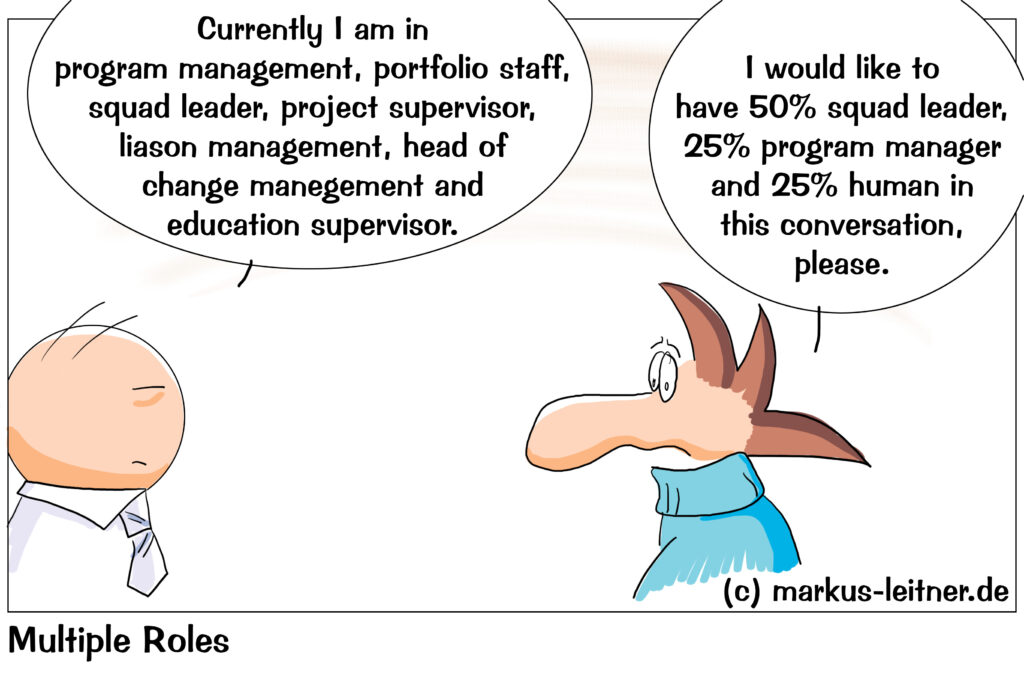

We have learned – and the Scrum Guide requests it – that we have to distribute our roles among different people. Unfortunately, in many organizations the reality is something completely different, and I am not talking about Scrum here, but the general problem that we tend do give our »more capable« colleagues all possible roles. Is that always a stupid idea, r is there a scenario in which it even makes sense to assign double roles? And if not – is there a way out of this mess?

We are all in a dilemma. On the one hand, we know that we are doing ourselves no favors by imposing several roles on individual colleagues, on the other hand, we all too often lack alternatives. We do not want to impose a role on anyone, so we ask certain people if they are willing to take on this new role (which in a way is forcing the roles on because hardly anyone ever says no). However, we always ask the same people because they are the ones who have done a good job in the past, who have shown they accept responsibility, and who we know we can rely on.

With that we always end up in a kind of hero organization. A few take responsibility while many others follow. However, these forms of organization are extremely vulnerable because the loss of a single one of these key players can hardly be compensated for. We always notice this when a colleague is on vacation and then nothing happens in whole areas and all grinds to a halt. This is a sign that an organization is unable to make up for the loss of a particular colleague. In general, this happens when there are too many roles and associated responsibilities on individual shoulders.

Even though we know this, we continue to give the same people new roles over and over again. This is the direct route to hell, isn’t it?

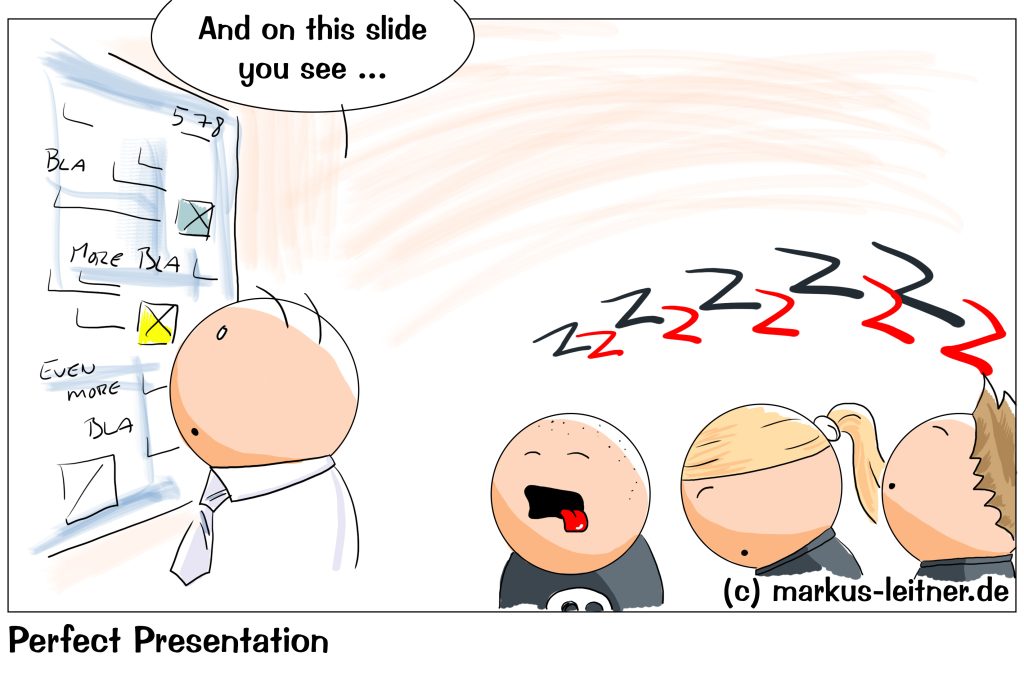

We not only take the risk that the bus factor becomes unbearably high – how great is the damage if the bus runs over the colleague, we also overload the colleague concerned. This is, of course, primarily harmful to the person. Burnout is serious business. It is widespread, and often enough the reason is simply an overload of too many responsibilities. But the whole thing is also detrimental to the organization. Even if the worst does not come, the colleague cannot fill all of his roles with full strength. Things are left lying around longer than necessary, things are only done at half power, things are done at the last minute. That makes it error-prone, and the quality suffers anyway.

It also makes working together more difficult. Conflicts of interest arise, and when you talk to such a person, you never know what hat they are wearing. We could still discuss the negative consequences for hours, but that will not be necessary. I think we all agree that piling up roles and responsibilities on individuals is not a good idea.

Nevertheless, we stick to the pattern of always giving the same people more and more responsibilities. When asked why we are doing this, we always answer that we have not found another.

I think now is the time to think about solutions. And it is here like it is with any other problem: there are many ways that lead to Rome.

In our organizations there is a lot of undiscovered and untapped potential in our colleagues. Through our hierarchical constructions (which are always there, even if we claim to have flat hierarchies), we create a barrier. Only when you have overcome this you will be shortlisted for most roles and will be asked.

Of course, half of you will scream out now and say that your company has a management trainee program or whatever. Let’s ask what you have to do or what requirements you have to meet in order to get there. Completed degree – why? Recommendation by the manager who is so far removed from the teams that he/she only comes for a personal meeting once a year? A personal application followed by a selection process – according to which criteria? Talent and potential is extremely difficult to judge.

Please do not get me wrong, there are also very good programs for young talent. Most of the ones I have encountered in the past, however, have been highly inadequate because they have set up hurdles themselves instead of removing them. We also have to look for a way not only to find colleagues who would be willing to take on responsibility, but also to recognize their hidden potential. We will not achieve this through programs, but through direct personal contact.

An example: A Scrum Master works closely with the team. He or she sees who on a small scale – and that is what it is all about – repeatedly takes on responsibility constantly, organizes things, and makes sensible and targeted contributions. These people automatically take on leadership roles within the team, even if we do not officially know such things, but of course there are internal team structures and hierarchies.

It is precisely the people who take on responsibility on a small scale – unnoticed by the larger structures – day after day that we are looking for. However, we ask those, who are close enough to the teams and the hidden potential, not about their recommendations or about the people they notice.

So that we understand all of this correctly, if I have to apply for a management trainee program, I will automatically address those who are thinking about their careers. However, we do not reach those who already take on responsibility in their immediate environment every day, because they do not think about their own careers in this way. These colleagues just do the things that need to be done, and it is precisely these people that we want.

So let us start now, ask our Scrum Masters or others who are very close to the teams about the people who take on small-scale responsibility in this form, and our problem is solved?

Well, not quite.

On the one hand, we have to notice that these people exist, and not everyone sees them. On the other hand, we then have to start carefully. If I have only played in small bars as a musician and suddenly I am on a huge stage in a stadium, it could backfire. The size of the task might put me off. So we have to proceed very slowly and carefully, find the next larger scaled level on which one can act. Maybe a role within a team leads to a role for a few teams (maybe three or four). That is not very scary, the size of the task does not seem daunting.

At the same time, people who already have a role can move up to the next larger scaled level for them and perhaps relieve another one who has two or more roles.

The whole thing is a long process that never ends, that you have to push again and again, that you have to watch out for over and over again. We will not be able to solve the problem of too many roles on too few shoulders with one big bang in a very short time. The relief for these colleagues must grow. It just takes time.

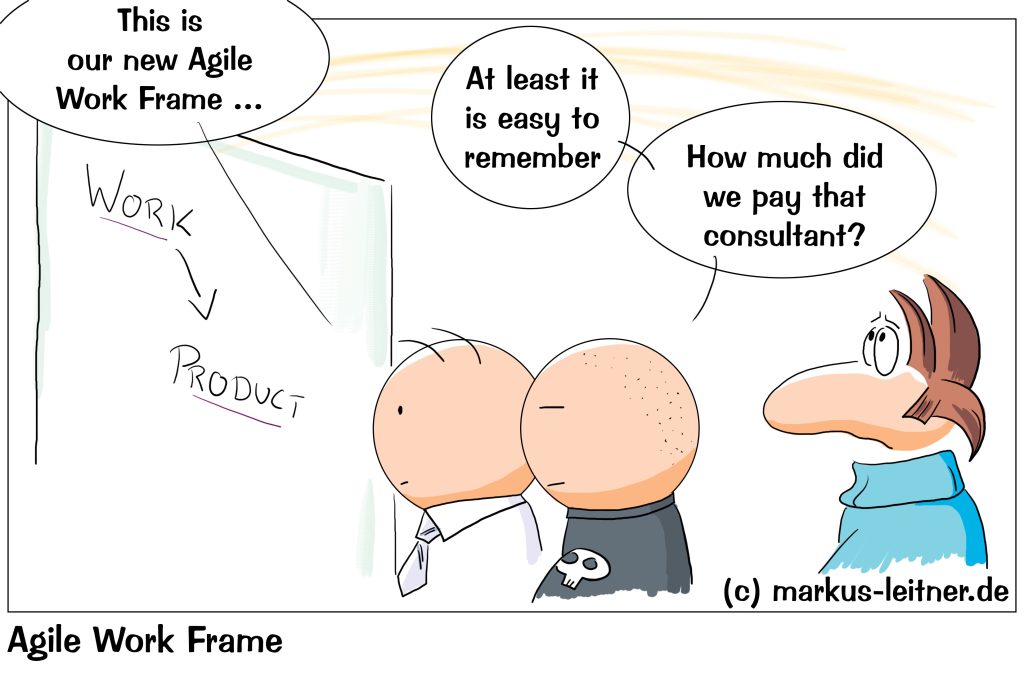

Finally, the question of whether there are meaningful combinations of roles. The simple answer to that is no. When two roles are so close together that the same person can reasonably take on them, then it is probably best to combine them into one. Our roles are also subject to Inspect & Adapt. When we find we need to change them, we change them. We do not do this every day as we like, but when there is a good reason we adjust things.

Core: We pile roles on individuals because we lack alternatives. In general, however, there are enough alternatives that we are simply not aware of. People who are close to a team can find people who take on responsibility in their environment over and over again. These are suitable for roles on the next larger scaled level. In this way, we are gradually creating a larger pool of people who can take on responsibilities.

If you need any assistance or want to know more, just speak to me.